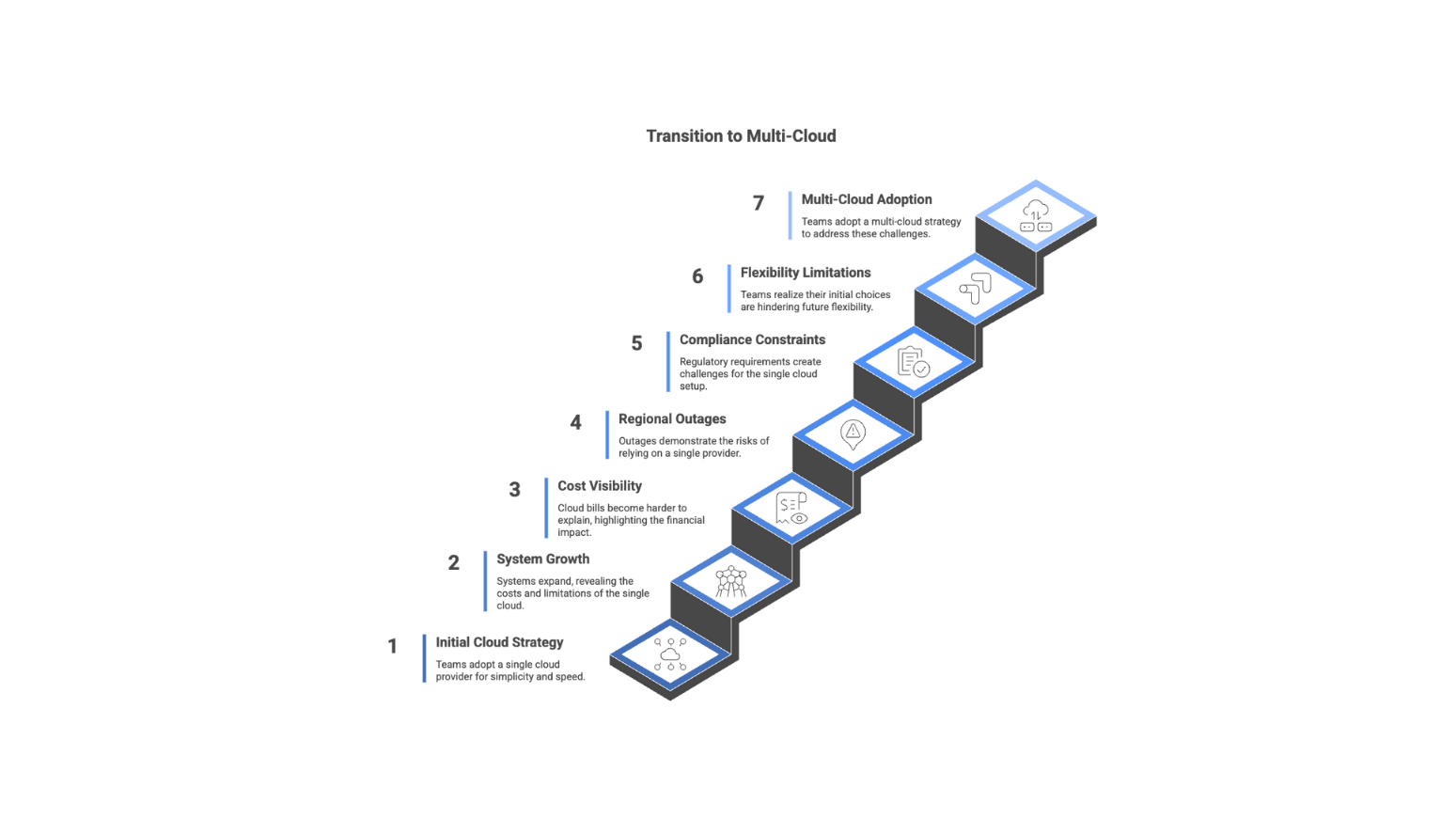

For a long time, cloud strategy followed a simple rule: pick a provider, commit fully, and optimize inside that ecosystem. For many teams, that approach is still reasonable. A single cloud keeps architecture simpler, reduces cognitive load, and lets teams move quickly without constantly revisiting foundational decisions.

The problem is what happens later.

As systems grow, the cost of those early decisions becomes more visible. Cloud bills get harder to explain. Regional outages stop feeling theoretical. Compliance requirements introduce constraints that don’t align neatly with a single provider’s footprint. And over time, teams realize that choices made for speed are now limiting flexibility in ways that are expensive to undo.

This is usually when multi-cloud enters the conversation, not as a trend, and rarely as a proactive strategy. More often, it’s a response to pressure that has been building quietly for years.

What Multi-Cloud Actually Means

In practice, multi-cloud means running workloads across more than one public cloud provider — on purpose.

That last part matters. Multi-cloud isn’t about hedging every bet or duplicating systems everywhere. Teams that take that approach often end up building complexity that solves hypothetical problems while creating very real operational ones.

Most real multi-cloud environments are uneven. One provider tends to remain primary. Another is introduced to serve a specific need, such as analytics, regional presence, or disaster recovery. Over time, that second footprint grows — sometimes intentionally, sometimes not.

It also helps to distinguish between multi-cloud and hybrid cloud, since the terms can get blurred. Hybrid cloud mixes on-prem infrastructure with public cloud services. Multi-cloud focuses on multiple public providers. Many teams end up with both, but the risks and tradeoffs aren’t the same.

Why Teams Actually End Up Going Multi-Cloud

Most teams don’t start out planning for multi-cloud. It usually shows up later, after a series of small decisions compound into something harder to reverse.

At first, everything lives in a single provider because it’s faster. That’s not a mistake. The trouble starts years later, when those early optimizations become constraints. The pressure usually comes from a few places

- Pricing becomes less predictable as usage grows unevenly

- Certain managed services turn out to be stickier than expected

- Regional outages feel less hypothetical after the first real incident

- Compliance introduces requirements that don’t map cleanly to one footprint

At that point, teams aren’t chasing flexibility for its own sake. They’re trying to regain it.

There’s also a quieter motivation that doesn’t always get stated directly. Over time, organizations realize how much leverage a single provider has once switching costs become real. Multi-cloud doesn’t eliminate that dependency, but it can soften it enough to change future conversations.

Not everything needs to move. In fact, most things shouldn’t. The goal is rarely symmetry. It’s optionality.

👋 What’s driving your cloud decision right now?

Tell us what you’re running today and what’s prompting the conversation—cost, reliability, growth, or something else? We’ll help you think through next steps.

Trusted by tech leaders at:

When Multi-Cloud Makes Sense — and When It Doesn’t

Multi-cloud works best for organizations that already feel the limits of a single-cloud approach. These are usually teams with multiple production systems, clear ownership models, and a baseline level of operational maturity.

They’re not experimenting with cloud anymore. They’re running businesses on it. This often includes global platforms, regulated industries, and teams that have already invested heavily in automation and platform practices.

Where multi-cloud struggles is earlier in the lifecycle. For small teams still validating product-market fit, the added overhead rarely pays off. The same is true for organizations that are still wrestling with basic cloud hygiene.

A few warning signs keep popping up:

- Environments aren’t consistent across teams

- Deployments already feel fragile

- Ownership is fuzzy even in a single cloud

- The motivation sounds like “just in case”

Multi-cloud amplifies whatever is already there. If the foundation isn’t solid, it becomes obvious quickly.

In the real world, multi-cloud architectures evolve incrementally. Often, a second provider is introduced for a specific reason: analytics, regional reach, or disaster recovery. Production traffic may still flow through a single cloud, with the second environment acting as insurance rather than a peer.

More advanced setups distribute traffic across providers, but these designs demand much stronger operational discipline. They’re harder to reason about, harder to test, and harder to operate under stress.

Another decision teams face is how centralized to be. Some standardize identity, CI/CD, and observability across clouds. Others allow cloud-specific tooling and integrate at higher levels. Either approach can work, but inconsistency without intent usually becomes painful later.

The Challenges Teams Underestimate

This is where the theory starts to break down.

Multi-cloud doesn’t fail because the technology isn’t ready. It fails because it quietly increases the number of decisions teams have to make every day. Different consoles. Different defaults. Different failure modes.

In practice, the friction shows up in small, cumulative ways:

- Incidents take longer to untangle

- Cost conversations get fuzzier, not clearer

- Monitoring spans too many tools

- A few people quietly become critical infrastructure

Operational complexity is usually what teams feel initially. Troubleshooting requires a broader context. Deployments take longer to reason about. What used to be a single incident now involves coordination across platforms.

Cost is often the next surprise. Not because multi-cloud is inherently more expensive, but because visibility fragments. Each provider has its own billing language and optimization levers. Understanding where money is actually going takes more time than most teams expect.

Security and identity add another layer. IAM models look similar across providers, but behave differently in practice. Policies drift. Auditing becomes harder. The shared responsibility model gets blurrier, not clearer.

And then there’s the human side. Multi-cloud raises the bar for platform maturity. Without clear ownership and strong standards, teams end up relying on institutional knowledge rather than systems, introducing a different kind of fragility.

A More Sustainable Way to Approach Multi-Cloud

Teams that succeed with multi-cloud usually start somewhere other than architecture.

They start by being honest about the business problem. What risk are we actually trying to reduce? What constraint are we responding to? What changes if this works?

From there, standardization becomes critical. Infrastructure as code, consistent deployment patterns, and shared conventions matter more in a multi-cloud world than in a single-cloud one.

Portability needs to be treated pragmatically. Some abstraction helps. Some lock-in is acceptable. The goal isn’t to make everything movable, but to make future decisions less painful than they would otherwise be.

A few practices recur in successful efforts.

- Clean up the first cloud before adding another

- Introduce the second provider for a narrow, clear reason

- Invest early in observability and cost visibility

- Add governance before sprawl appears

Multi-cloud works best when it evolves in phases. When it’s forced all at once, teams tend to inherit complexity they don’t yet know how to manage. Multi-cloud isn’t about being cloud-agnostic. It’s about being intentional.

For the right organizations, it creates leverage, resilience, and long-term flexibility. For others, it becomes a drag, slowing teams down and obscuring accountability. The difference is rarely tooling. It’s clarity, discipline, and timing.

How Curotec Can Help

If you’re starting to feel the limits of a single-cloud setup—or questioning whether multi-cloud is actually the right next step—it’s usually worth talking it through before touching architecture. Curotec helps teams sort through that moment. Sometimes the answer is multi-cloud. Sometimes it’s fixing what’s already there. The important part is making the decision deliberately, before complexity makes it for you. Contact us to start the conversation.